Late yesterday, wildlife advocates filed a lawsuit against the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (the Service) over its failure to take any action in response to a 2016 court order striking down the agency’s exclusion of Canada lynx habitat in the species’ entire southern Rocky Mountain range from designation as critical habitat. This habitat is essential for the wildcat’s recovery.

“Nearly four years later, the Fish and Wildlife Service has not lifted a finger to comply with the court’s order to reexamine the southern Rockies for critical habitat designation for lynx,” said John Mellgren, attorney at the Western Environmental Law Center. “A federal judge unambiguously ordered the Service to fulfill its mandatory duties under the Endangered Species Act related to potential critical habitat for lynx in the southern Rockies, and the Service has not done so. Colorado, in particular, is full of excellent lynx habitat that deserves a heightened level of protection to help foster lynx recovery.”

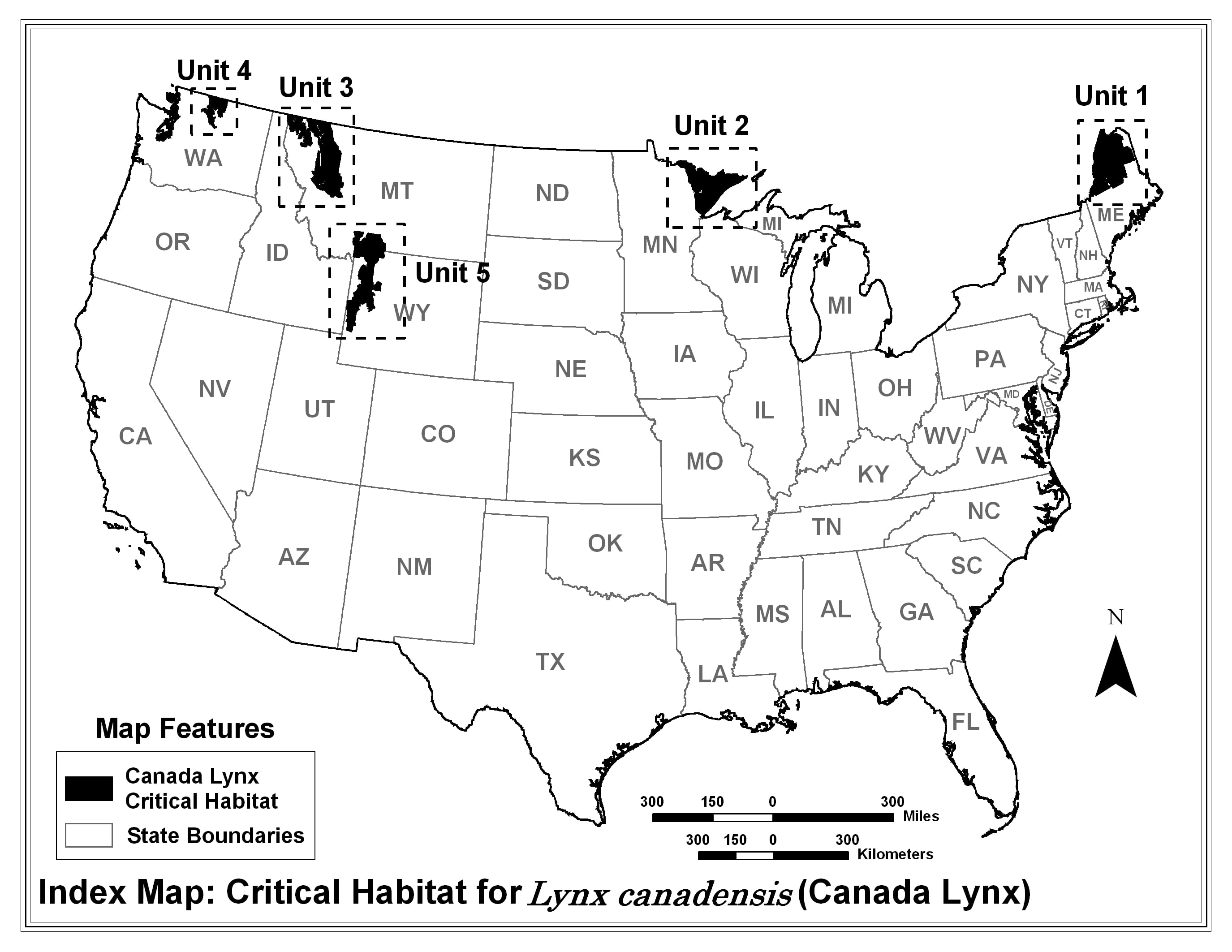

Critical habitat is area designated by the federal government as essential to the survival and recovery of a species protected by the Endangered Species Act (ESA). Once designated, federal agencies must make special efforts to protect critical habitat from damage or destruction. In 2014, the Service designated approximately 38,000 acres of critical habitat for threatened lynx, but chose to exclude the lynx’s entire southern Rocky Mountain range, from south-central Wyoming, throughout Colorado, and into north-central New Mexico. These areas are vital to the iconic cat’s survival and recovery in the western U.S., where lynx currently live in small and sometimes isolated populations.

“Lynx were virtually eliminated from Colorado in the 1970s as a result of cruel trapping, poisoning and development that lay waste to their habitat,” said Lindsay Larris, wildlife program director at WildEarth Guardians, based in Denver. “Despite efforts to reintroduce these elusive cats to their native habitat from 1999 to 2010, without federal critical habitat protections, the lynx may never truly have the opportunity to recover in the Southern Rockies.”

Perplexingly, the Service’s latest designation decreased existing protections by 2,593 square miles compared to a 2013 plan. In doing so, the Service excluded much of the cat’s historic and currently occupied, last best habitat in the southern Rockies and other areas from protection. In its 2016 order, the court found the Service failed to follow the science showing that lynx are successfully reproducing in Colorado, and therefore excluding Colorado from the cat’s critical habitat designation “runs counter to the evidence before the agency and frustrates the purpose of the ESA.”

The court challenge seeks to install hard, legally binding deadlines for the Service to publish a lynx critical habitat rule, along with frequent progress reports, also legally binding, due to the agency’s long record of negligence and delay on the subject of Canada lynx recovery actions. WildEarth Guardians, the San Juan Citizens Alliance, and Wilderness Workshop are represented by the Western Environmental Law Center on this case.

Contacts:

John Mellgren, Western Environmental Law Center, 541-359-0990, mellgren@westernlaw.org

Lindsay Larris, WildEarth Guardians, 310-923-1465, llarris@wildearthguardians.org

Canada lynx background:

Canada lynx, medium-sized members of the feline family, are habitat and prey specialists. Heavily reliant on snowshoe hare, lynx tend to be limited in both population and distribution to areas where hare are sufficiently abundant. Like their preferred prey, lynx are specially adapted to living in mature boreal forests with dense cover and deep snowpack. The species and its habitat are threatened by climate change, logging, development, motorized access, and trapping, which disturb and fragment the landscape, increasing risks to lynx and their prey.

The Service first listed lynx as threatened under the ESA in 2000. However, at that time the Service failed to protect any lynx habitat, impeding the species’ survival and recovery. Lynx habitat received no protection until 2006, and that initial critical habitat designation fell short of meeting the rare cat’s needs and the ESA’s standards. After two additional lawsuits brought by conservationists challenging the Service’s critical habitat designations culminated in 2008 and 2010, a district court in Montana left the agency’s lynx habitat protection in place while remanding it to the Service for improvement. This resulted in the habitat designation that was remanded for improvement again in 2016.

In 2014, the U.S. District Court for the District of Montana also ruled that the Service violated the ESA by failing to prepare a recovery plan for lynx after a more than 12-year delay. The court ordered the Service to complete a recovery plan for lynx or determine that such a plan would not promote the conservation of lynx by January 15, 2018. The Service ultimately determined that a recovery plan would not promote the conservation of lynx, thereby depriving lynx of a recovery plan.

The Service’s 2017 Species Status Assessment analyzes lynx population centers’ “probably of persistence”—their likelihood of surviving to the year 2100—under our present regulatory framework as follows:

Unit 1: Northern Maine – 50%

Unit 1: Northern Maine – 50%

Unit 2: NE Minnesota – 35%

Unit 3: NW Montana/SE Idaho – 78%

Unit 4: Washington – 38%

Unit 5: Greater Yellowstone – 15%

Unit 6: Western Colorado – 50%

Indeed, the lynx Species Status Assessment paints a bleak picture for lynx, noting only one geographic unit (Unit 3 – MT and ID) “has a high (78%) probability of supporting resident lynx by 2100” and noting the remaining geographic units “were deemed to have a 50 percent or greater likelihood of functional extirpation…by the end of the century.” SSA at 6.

Studies show species with designated critical habitat under the ESA are more than twice as likely to have increasing populations than those species without. Similarly, species with adequate habitat protection are less likely to suffer declining populations and more likely to be stable. The ESA allows designation of both occupied and unoccupied habitat key to the recovery of listed species, and provides an extra layer of protection especially for animals like lynx that have an obligate relationship with a particular landscape type.

Canada lynx photo for media use (Credit: USFWS/Dash Feierabend, larger version)